Wow, it’s just wild how much has happened since we all came together last week! I’m sure the microscopic threat called SARS-CoV-2 has changed the daily lives of most of us and it’s hard to get back to work in our home offices. I was wondering how much space this ubiquitous topic should get in my blog post. Considering the vast amount of universities and schools all around the globe that are now in the process of transitioning to online learning, it is definitely worth examining the current EdTech processes from a critical perspective. However, as I am sure that the Coronavirus will dominate our discussion next week anyways, I will only touch on this topic at the end of my post with some open questions and will, instead, try to give you an insight into our readings.

Even though it feels like it’s been a very long time since we’ve had our last meeting, you may remember that we read texts about the Thoma Bravo’s acquisition of Instructure, the provider of Canvas. We learned about the resistance of educators and shareholders that were worried about the sale of Instructure and its implications for the strategies of the company and its LMS. In this week’s reading, Phil Hill examined how Instructure reacted to this criticism, and he seemed to be surprised about the explicitly profit-driven framing of the company’s response. Instructure is straight-forward about their goals: “the Board of Directors has one priority: maximizing value for our stockholders”. I was wondering if Hill is genuinely surprised that a corporation’s primary objective is the increase of their revenue or if he is rather surprised about the fact that they communicate is such a transparent way. In either way, the company’s focus on monetization and profit-making reveals that even a company like Instructure that was initially thought to be “different”, as it brought new vibes into the LMS market, is eventually pushed by market forces to follow the rules of neoliberalism. But can we conclude from this that EdTech companies care more about money and power, then about things like pedagogy and data privacy?

– Sure, any answer to this question would simplify the complex settings in which EdTech companies operate. However, it is definitely worth scrutinizing the economic interests of corporations involved in the education sector. Ben Williamson’s paper on Silicon Valley start-up schools is a good example of such an effort, as it examines the role of money and political influence in the EdTech world. He demonstrates how Silicon Valley networks are using their financial and technical means to push a “technocratic mode of corporate education reform” by creating their own schools. With executives and engineers from the tech industry as executives and staff, big tech firms try to restructure school institutions based on tech sector market logics. The ultimate goal is to “scale up” these projects and create a more effective, data-driven alternative to traditional educational institutions. Critically, the narrative used by these companies reveals that their “algorithmic imaginaries” of the future of K-12 education do not envision a renewed public education. Instead, public schooling is described as a “dangerously broken system” and private startup schools are considered to be the cure. I think the apparent conflict of interests that arises when these companies promote their schools in a highly lucrative private education market does not need further elaboration.

How desperately tech vendors are waiting to expand their role in education can also be seen in the study by Jennifer Morrison and her colleagues at the Johns Hopkins University. While administrators and executives in public education are mostly satisfied with the procurement of EdTech, providers are “extremely dissatisfied”. Almost 80% of the vendors expressed their dissatisfaction with the “district’s processes for identifying, evaluating, and acquiring needed ed-tech products” and more than 70% are dissatisfied with “the time required to complete procurement processes and bring products to end-users”. The latter directly mirrors Williamson’s observation that “corporate philanthropists (many from successful technology companies) are impatient with public bureaucracies and have focused instead on creating a broad network of private and nonprofit alternatives for developing and running schools.”

It may be no surprise to see that the fast-paced business world conflicts with long-term decision-making procedures in public administration but the consequent division of educational institutions into private high-tech and public low-tech schools is worrisome. Thus, we should ask ourselves: How do we bring together private and public actors without losing control of our public institutions and without failing to take advantage of private products? The study by Morrison et al. suggests that improved EdTech procurement processes may be able to manage this task. However, according to the authors, there are currently various barriers in procurement processes, such as the insufficient integration of the end-user experiences, the lack of comprehensive assessments of the schools’ needs and mostly inadequate evidence of the products’ pedagogical implications.

The Gallup survey, commissioned by the NewSchools Venture Fund, touches on several of these aspects. It examines the opinion of end-users, teachers and students, and aims to provide evidence for the perceived effectiveness of digital learning tools. The study even claims to “provide critical information for educators, leaders, developers and entrepreneurs to maximize the effectiveness of digital learning tools that support teaching and learning today.” Yet, I doubt this report can bring together private and public actors in a well-balanced, meaningful way. Instead, it seems to fall into the category of “non-rigorous evidence”, which Morrison et al. criticize for its distortion of decision processes. This report is funded by philanthropies like the Gates, Dell, and Chan Zuckerberg Foundation and should be used with scrutiny. Even though some findings of the study may indeed be useful for decision-makers, the technocratic framing of this report reveals its support from the Silicon Valley.

One aspect that I found to be particularly suspicious was the use of “effectiveness”. The words “effective” and “effectiveness” are found more than a 100 times in this report and findings like “Most teachers, principals and administrators think digital learning tools are at least as effective as non-digital learning tools” are praised by the authors. Yet, as the authors fail to provide a definition of effectiveness, these statements raise more questions than they offer answers for critical readers. If digital tools were just as effective as non-digital tools, could I switch to digital learning and nothing would change? Do teachers and administrators even perceive effectiveness in the same way? Unfortunately, however, “effectiveness” just remains a buzzword in this study complying with the technocratic narrative of Silicon Valley corporations. Considering this, the report is a perfect illustration of how difficult it is to make well-informed decisions on how to include EdTech in schools in a world that is dominated by powerful companies, which, eventually, will always a have financial interest in selling their products.

–

It is clear that the EdTech procurement decision-making processes need sufficient time to assess products independently and think through their long-term effects. But what happens if there is just not enough time to consider all of the implications that the use of digital learning and teaching tools might have? I think it is a question that we should ask ourselves in the current crisis.

In my opinion, Morrison et al. offer a useful guideline for EdTech procurement processes:

1. Assessment: What ed-tech product do we need?

2. Discovery: What ed-tech products are available for our needs?

3. Evaluation: Which available products are the best fit?

4. Acquisition: Can we acquire the products that we select in a timely manner?

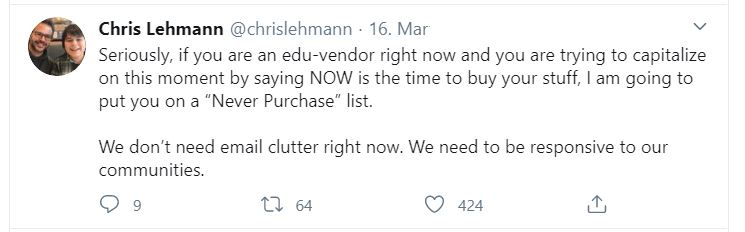

Is it possible to go through all of these steps sufficiently in the current crisis, now that the transition to online learning needs to happen asap? What happens if administrators and executives skip several steps of this framework? What will be the long-term effect of this rapidly implemented online teaching environment? How should EdTech vendors behave in this situation?

I am already looking forward to discussing these questions and the readings with you on Tuesday!

Warm thoughts and stay healthy!

– Lucas