When I was reading the materials for this week, one definition in Pat Reid’s article stood out for me:

“Educational technology is the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using, and managing appropriate technological processes and resources.”

Ritzhaupt, Albert D., et al. “Development and Validation of the Educational Technologist Competencies Survey (ETCS): Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education, vol. 30, no. 1, Apr. 2018, pp. 3–33. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/s12528-017-9163-z.

The word that really resonated with me was “ethical”. In all the failures of ed tech we’ve read about, the ethical component was the most problematic to me. Ed tech should be used to promote learning, but it many cases it becomes an exploitative practice towards students and faculty. In Austerity Blues, for example, the authors expose how UCLA administrators failed to inform the Faculty Senate about the legal negotiations with THEN-OLN. Another example of failed Ed Tech, the SJSU-Udacity experiment, caused faculty uproar. The SJSU Academic Senate protested the administrator’s power to unilaterally impose new pedagogical practices and to monetize the faculty’s intellectual property without their consent.

I thought about Audrey Watter’s proposition to have a “Hippocratic Oath for Ed Tech”. The author draws a comparison between educators and healthcare professionals, who share the mission “First, do no harm”.

Coming from a background in Comparative Literature, I decided to bring the comparison even further, and two words popped up in my mind: “comitato etico” (“ethics committee”). In my research to discover what an ethics committee exactly was, I was surprised by two facts:

- It is only used for medical studies! For some reason, I thought that every public institution needed an ethics committee – how optimistic of me.

- My beloved EU has a directive about ethics committees and how they work.

The Ethics Committee

The definition of an Ethics Committee is in Article 2 of DIRECTIVE 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament (emphasis mine):

“(k) ‘ethics committee’: an independent body in a Member State, consisting of healthcare professionals and non-medical members, whose responsibility it is to protect the rights, safety and wellbeing of human subjects involved in a trial and to provide public assurance of that protection, by, among other things, expressing an opinion on the trial protocol, the suitability of the investigators and the adequacy of facilities, and on the methods and documents to be used to inform trial subjects and obtain their informed consent”

Ervine, Cowan. “Directive 2004/39/Ec of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004.” Core Statutes on Company Law, by Cowan Ervine, Macmillan Education UK, 2015, pp. 757–59. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1007/978-1-137-54507-7_21.

What does independent mean?

- The ethics committee and the research center must not be in a relationship of hierarchical subordination

- There needs to be the presentce of personnel external to the research center

- Absence of conflict of interest

- Committee members must not have an economic interest in pharmaceutical companies.

The goals of the ethics committee

- Guarantee the feasibility of the project, from an ethical and a scientific standpoint;

- Protect the rights of the subjects of the research;

- Ensure an appropriate relationship between the research center and the sponsor of the study.

How can we translate this to Ed Tech?

The Ed Tech Ethics Committee:

- Is an independent body

- no hierarchy among members

- no conflict of interest: committee members and the institution must not have ties with Ed Tech vendors

- Is composed by university personnel (faculty, adjuncts, administrative staff) and a representation of students

- Is responsible for ensuring:

- Respect of faculty and students’ rights (ex. intellectual property, privacy)

- Pedagogical effectiveness

- Needs to provide public assurance

- Accountability

- Transparency

- Its goals are:

- Ensuring the economic, pedagogical, and ethical feasibility of a product or service

- Defend the rights of faculty, staff, and students.

- Ensure an ethical relationship between the institution and the vendors.

CUNY Graduate Center’s First Ethical Committee for Ed Tech: a Simulation Game

Part of my MA in Italy was dedicated to videogame semiotics and game studies, especially as far as boardgames are concerned. Thanks to Professors Peppino Ortoleva, Ivan Mosca, and Riccardo Fassone, I learned how helpful games can be in understanding complex issues.[1]

Therefore, I thought it might be interesting to simulate how an Ethics Committee might work in the Ed Tech field. Yes, it’s going to be nerdy. And yes, I’ve been watching too much Star Trek these days.

The Scenario

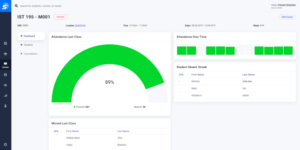

During a global pandemic (lol) the needs of the CUNY GC have changed. And Blackboard has crashed. The GC needs a new platform for distance learning and to ensure the safety of students and personnel. Ed Tech company Whiteboard offers CUNY GC a service similar to Blackboard, but harder, better, faster, stronger. It also offers a mobile app that tracks GC students’ and faculty to monitor the spread of Coronavirus, similar to what Apple and Google are building now.. The Ed Tech team at CUNY GC creates an Ethics Committee to evaluate the proposal.

Players and their Roles:

- The Vendor: Prof. Waltzer. I thought it would be interesting to have him reverse his usual role. The vendor offers a brief presentation of the product and is available to answer questions from the Ethics Committee.

- The Ethics Committee: I’m assigning the roles according to the list on our group in the Commons. Also, feel free to reach out in the comments if you wish to change roles or if you can’t make it to class on April 21. The Ethics Committee members ask questions to each other and to the Vendor. All you need to do is prepare some questions or discussion prompts beforehand.

- Student Representatives: Hyemin, Lucas

- Faculty: Carolyn, Jelissa

- Adjuncts: Jason, Kathleen

- Administrative Staff: Zach, Anthony

- Librarians: Shani

- Guide: me. I’ll be there to coordinate the discussion, help out, and let you know when it’s time to make a decision.

The Goal

This is a cooperative game. People need to discuss to come to a shared solution.

Can’t wait to see you all on Tuesday…and I hope the game works!

[1] By the way, Ortoleva coined the term homo ludicus and did extensive research on the ubiquity of game and play in contemporary society, in case you’re interested!