As far as education today goes, it seems uncontroversial to assert that ed-tech companies tend to suffer from bouts of what one might call a messiah complex. Looking past this apparent attempt to “innovate” the educational establishment by “sparing” educators from their late-night grading binges, it isn’t hard to discern a more self-absorbed, profiteering agenda at work. Framing this conversation well, John Warner picks apart the efficiency-happy spiels of ed-tech startups, like Knewton and Amplify, by focusing on the human dimension of education:

The driving values of all of these teaching machines is “efficiency”, but it is difficult to reconcile the value of “efficiency” with learning. Education is an ongoing process, not a product, and what we learn as we stumble off the path is often more valuable than when we are toeing the line. Do we value “efficiency” in our relationships with our families? Is our most profound love “efficient”?

Empowering students to assume an active and earnest role in their continued education does not, in other words, come easy. There are no circuitous work-arounds when it comes to engaging learners who are as diverse and multifaceted as ever before. So when companies wave around their magic wands, tout their one-size-fits-all solutions, and co-opt progressive educational phrases like “personalized learning,” it should be cause for concern. Accordingly, we should be critical when faced eye-to-eye with shortcuts that purportedly make our job as educators easier and more efficient. More often than not, that is to say, educational “miracles” come at a serious cost — a cost that students will have to pay, never really having a choice in the matter to begin with.

What is more, look to Jim Groom’s skepticism regarding the self-proclaimed advent that is the “Next Generation” of Learning Management Systems, Blackboard 8, which only seems to echo the technocratic rhetoric of so many proprietary tools before it. Confident in its sole capacity to “enhance critical thinking skills” and “improve classroom performance,” this new edition of Blackboard goes so far as to tacitly step into the shoes of tomorrow’s new and improved educator. Such is the anthropomorphic rhetoric of propriety ed-tech, in which for-profit tools and resources advertise themselves as effective substitutes for the engaged efforts of embodied educators. To the contrary, Groom notes,

These things are not done by technology, but rather people thinking and working together. Our technology may afford a unique possibility in this endeavor by bringing disparate individuals together in an otherwise untenable community, yet it doesn’t enhance critical thinking or improve classroom performance, we do that, together.

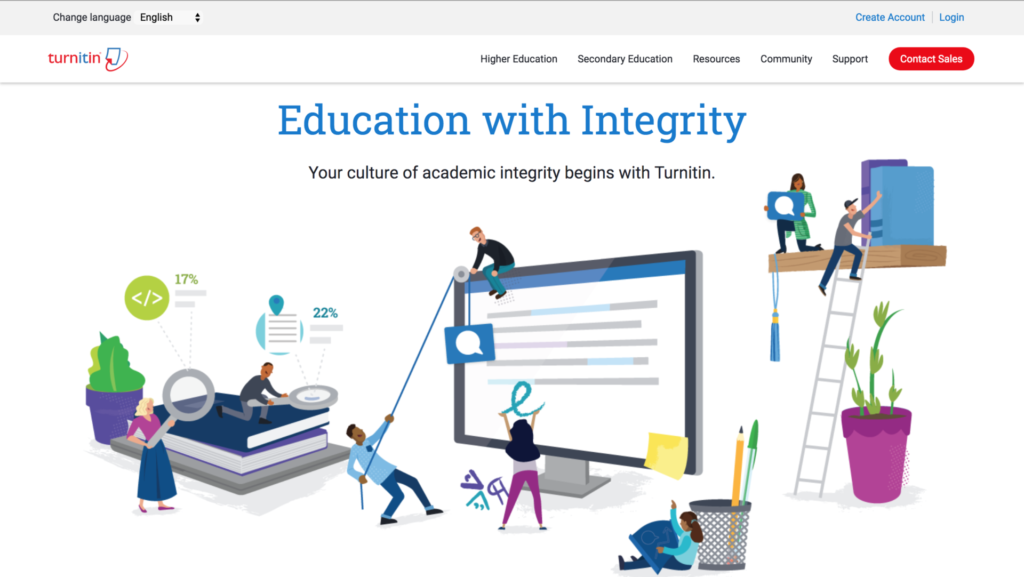

Groom goes on to emphasize this point, blasting Blackboard for its attempt to “commodify the labor of others” under its own name, in turn bolstering “the idea that educational technology ‘is about the technology,’ ” which, of course, it is not. Looking closely, we can see this trend present in several of our readings for this week. The landing page for Turnitin‘s website yields a good example. Upon entering the site, we’re met with a presumptuous slogan — “Education with Integrity” — in conjunction with a tech-centered graphic in which students are dwarfed by a giant computer whose monitor displays Turnitin’s implied interface.

The combined rhetorical effect of this page is complex and problematic and kind of bizarre. First up is the slogan, which seems to imply that education without a subscription to Turnitin is one that lacks integrity, as if to say the relationship between teachers and learners is not the bedrock of academic honesty. The centeredness of the floating monitor — with Turnitin’s various features swarmed by seemingly excited (and faceless) learners — only works to reiterate this message: even in the visual absence of a human educator, technology still manages to educate, to edify and to impassion. Hey, apparently, it can even motivate students to reinvent the pulley system! Ultimately, the rhetoric of this landing page is so idealized as to beckon toward some bizarre techno-utopian future where students passionately gather round technology as their much sought-after savior. Meanwhile, in my experience, students scowl at the mere mention of Turnitin. Why? Because Turnitin forges an air of distrust and doubt among students and teachers, making learners feel like they’re bugs under some sort of plagiaristic microscope. In any case, the problems here are so loud that they speak for themselves.

In looking for recourse among our readings for this week, I found myself returning to Jesse Stommel’s call to mean what we say as educators, and to build substance into our promises as teachers. Or, as he writes:

When we use a word like “open,” or ones like “agency” and “identity”, these should not be just empty signifiers. We should be transparent, and even partisan, in our politics. Especially as educators. But we need not proselytize.

For far too many corporate entities, these words do become empty signifiers, not unlike a form of sophistic rhetoric aimed at exploiting students, teachers, and administrators for the sake of an extra buck. That said, the best we can do in response is to act in good faith and in the genuine interest of our students, not only as learners but also as human beings. To always recognize their humanity during this process is a continued act of affirmation — and to settle for anything less is to do a disservice to a world of people who deserve so much more.

With these thoughts in mind, I ask us to consider the following two questions:

- Where in our readings (or elsewhere) did you found there to be signs of empty rhetoric at the disposal of for-profit educational technology?

- How might we work day-to-day to diminish the foothold of propriety technology on education today?